Could the future of healthcare be tangled up in our abdomens?

An easily modifiable second genome lives in our gut. Controlling much more than what we think, potentially even controlling how we think, the microbiome has received its fair share of public attention over the last decade. We sat down with Jeremy Lim, CEO and co-founder of AMILI, Southeast Asia’s first and only precision gut microbiome company, to hear where he thinks microbiome research could take healthcare in the not-so-distant future.

Breakthroughs in our understanding of the microbiome occur frequently, with international journals publishing dozens of new studies a month. But, the science is still young, and exactly how these discoveries will translate into routine clinical practice is still being worked out. In recent years, the gut-brain axis, which describes the bidirectional communication system between the central nervous system (CNS) and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, has been generating a lot of excitement.

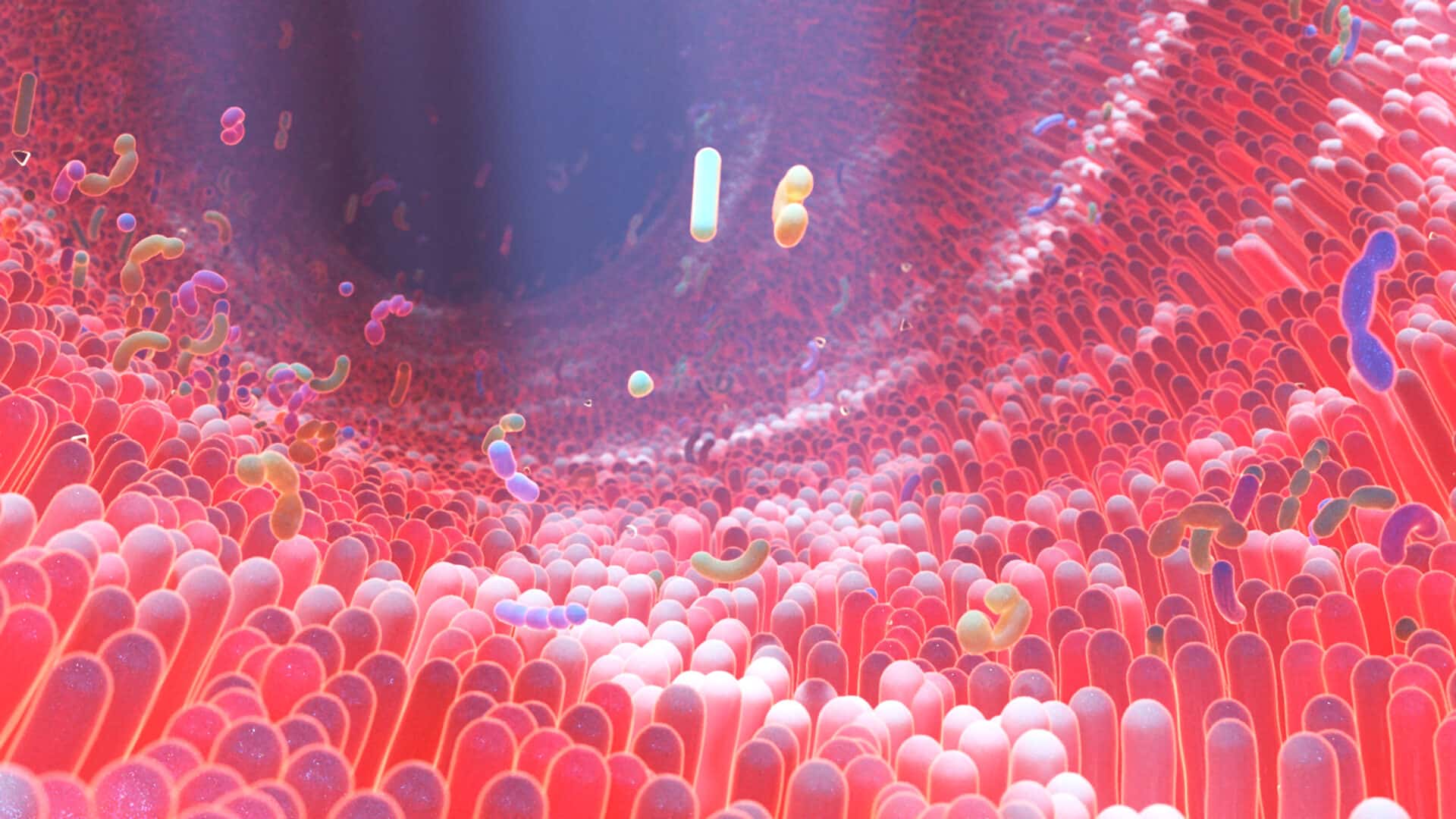

Research has revealed that the gut microbiota, which refers to the community of microorganisms inhabiting our GI tract, play a critical role in shaping the function and development of the CNS, and that disruptions in this communication system can have far-reaching effects on health and disease.

“Traditionally, we’ve taught medical students for generations that the world of sickness is divided into communicable and non-communicable diseases. However, given what we now know about the trillions of microbes that live in and around us, we’re just not so sure anymore.” Says Jeremy.

Why does science care about the composition of our gut microbiota?

The Human Genome project, one of the largest scientific collaborations in history, was an international, decades long effort involving tens of thousands of researchers who sought to sequence the entire human genome, consisting of around 3 million DNA base pairs. This extremely successful project produced overwhelming volumes of data, leading to the development of new technologies to manage it, such as high-throughput DNA sequencing, distributed computing, and bioinformatics software.

In the last decade, there has been an explosion of research in the microbiome, including the Integrative Human Microbiome Project (iHMP), which was established in 2014. The microbiome’s ‘second genome’ moniker is certainly well earned – when fully sequenced, a deeper understanding of the gut microbiome could have a similar impact on healthcare as the revelations uncovered by the Human Genome Project. However, the scale is quite different – the human genome has roughly 23,000 genes, versus the two to three million genes that comprise the microbiome.

This makes the task of unearthing its benefits far more complex, and computationally heavy, says Jeremy.

“One fully sequenced microbiome can be as large as one terabyte of data. Because of this, for the longest time, microbiome sequencing was something that only rich laboratories could undertake.”

The sheer volume of the many different types of biological data produced by microbiome research may be one reason why we’re seeing an explosion of interest in recent years. Moore’s law states that every two years, we can expect the speed and capabilities of our computers to increase, with costs going down. In the 1980’s, when research into the microbiome began to pick up pace, it cost US $3,398 to purchase a 10MB disk drive. Today, a terabyte of data, about the same as one fully sequenced microbiome, costs less than $100. Still, for many countries, especially developing economies in Asia, genomic and microbiome sequencing is at the very bottom of the priority list, despite clear links with many of the diseases burdening regional populations today.

Southeast Asia is fashionably late to the microbiome research party

The human genome is largely similar amongst people, but the microbiome differs significantly. Diet, lifestyle and the environment are key drivers, with genetics playing a relatively small role in determining our microbiome profile, according to Jeremy. This is one of the reasons Jeremy founded AMILI, Southeast Asia’s first and only gut microbiome transplant bank that is building the world’s largest multi-ethnic Asia gut microbiome database, in response to a lack of data from Asian populations.

“If you look at the number of studies that are going on around the world, they are really concentrated in North America, Europe, and more recently, China.” This is far from ideal, and if there were ever an avenue of research that required broader sample diversity, it’s the microbiome. Research in this field that ignores the developing world can significantly distort our understanding of human microbe interactions, warns a study published in the journal PLOS Biology.

“Ultimately, it’s a function of resource, in addition to the speed of adoption of medical technologies, that determines a region’s progress in microbiome research. In Southeast Asia, we’re not the richest region, so it isn’t surprising that we’re behind the curve and arrived to the party late. But the good thing is that when you’re behind the curve, there is every opportunity to learn from what others have done.”

How can a deeper understanding of our microbiome change healthcare?

The list of diseases that have been implicated to correspond with changes to our gut flora includes Type 2 diabetes, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease, and a variety of cancers. A fascinating frontier is the gut brain axis, and the link between the microbiome and mental illness.

In a 2022 study testing the effects of the gut microbiome on behaviour, researchers from the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena transplanted faecal samples from children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) into the stomachs of mice who had been raised in a sterile environment, with no microbiomes of their own. The offspring of the mice who inherited a microbiome from a child with autism were less social and displayed more repetitive behaviours than the control sample.

The authors of the paper concluded that colonisation with ASD microbiota is sufficient to induce hallmark ASD behavioural features of social dysfunction, communication impairment and repetitive and restrictive behaviours.

“Research like this begs the question, if we can transmit autism from a human to a mouse, could we transmit autism from a human to another human? And, do diseases cluster not just because of social behaviours, but also because we are transferring microbes? This research also provides us with a lot of hope, because if there are mental diseases that have a microbial element, then we know that we can modify the microbiome relatively easily in response.”

Not just a gut feeling

The longest cranial nerve in our bodies, the vagus nerve, extends from our brain stem to the abdomen and facilitates complex communication between our gut and brain. Compelling research uncovered in recent years, although still in its infancy, has shown that gut microbiota is responsible for regulating brain chemistry and influencing neuro-endocrine systems associated with stress response, anxiety and memory functions. Findings that show our microbiota can produce neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), have far reaching implications on treatments for mental health conditions ranging from anxiety and depression to schizophrenia.

“The way I see this evolving is that the well-read, well informed mental healthcare professionals will start to do two things. First, they will start to sequence their patient’s microbiomes to assess compatibility with various therapies. It is very clear that there are certain strains of microbes that are associated with poorer responses to the various treatments.”

Some psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia are associated with higher serum antibody levels to fungal pathogens, which are protein markers of bacterial translocation.

A 2018 study in Schizophrenia Research investigating gut microbiota as a biomarker in patients with schizophrenia found differences in the composition of the microbiome in people with schizophrenia versus that of healthy controls. Early life stress is a known risk factor for the development of numerous psychiatric disorders, and research conducted in rats suggests that this can produce long term changes in gut microbiota, which may contribute to the development of psychiatric illnesses like schizophrenia.

“The second thing I see happening is that enlightened healthcare professionals will start to take a much deeper food history of their patients, using diet as an adjunctive therapy to standard of care for mental illness. This doesn’t mean that the antipsychotics and antidepressants of today will no longer be necessary, but it might mean that for some mental diseases, we discover that the right place to intervene is not with the human, but with their microbes.”

What does all of this mean for healthcare?

While there is little we can do about the genes we inherited from our parents, our microbiome provides science with an incredible opportunity to modify the trillions of bacteria, viruses and fungi that inhabit our bodies, to potentially deliver us with improved healthcare outcomes and new ways of addressing health and diseases.

“As humans, we want not only to live long, but we also want to live well, and with healthier habits. This is where I think recognition of the importance of the human microbiome in preserving human health will become all the more evident, and this is because the microbiome is modifiable.”

AMILI’s research focus is currently in analysing its database, already the world’s largest multi-ethnic Asia repository and mining it for insights into health and well-being in Asia. AMILI also has large studies with hospitals and universities in Singapore and Malaysia, examining liver and gastro-intestinal diseases.

References:

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/apt.17049

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00018-021-04060-w

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2021.616883/full

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.869610/full

- https://ami-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1751-7915.13970

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/apt.17049

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23746484/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0889159117304804?via%3Dihub

The Impact Review Newsletter

Get highlights of the most important news delivered to your email inbox